Edward Hugh (Ned) Hanlon | Mount Pleasant ParkGolf CourseMaryland's Tournament CourseEstd. June 30, 1934 | Charles Augustin (Gus) Hook |

Edward Hugh (Ned) Hanlon | Mount Pleasant ParkGolf CourseMaryland's Tournament CourseEstd. June 30, 1934 | Charles Augustin (Gus) Hook |

Aerial view of Mount Pleasant Park in 1939 facing north northeast. Note: (1) No Starter's Shack!! [probably Gus's only design flaw] (2) One large green on #1 (3) Teeing ground for #2 is just west of #1 green (4) Northern Parkway and the ice rink aren't there; bridle path track is visible just south of #8 green and heading east toward #6 green (5) Part of the old Hillendale Country Club is visible north of #s 3, 4, and 5 (6) No refreshment stand at the turn (7) Foot bridge across Chinquapin Run below 14th tee (8) Another foot bridge across Chinquapin Run that allows access to the 17th green and 18th teeing ground (9) No bunkers protecting the 17th green (10) No cart paths (11) No practice green and bunker between #13, #16 and #18 (12) Perring Parkway isn't there.

|

|

| Mount Pleasant scorecard distances from 2008. | |

No. 6 green and part of No. 7 teeing ground at Mount Pleasant Park in 1938 or '39. In 1934, Mr. Hook piped a stream under #3 fairway. The pipe empties into a stream that parallels the seventh fairway and runs between #6 tee and green, eventually joining Herring Run. He built stone dams to trap the water into three shallow ponds. The dams fell apart from neglect and the ponds disappeared. All that remains is a swampy area infested with copperheads where dumb marshals hawk balls. A length of the bridle path can be seen above the golfer's heads. The area of the green is flanked on three sides by higher ground. Gus Hook's foresight and attention to detail is shown by the shallow depression he built around the green (a part of which is faintly discernible, between the golfers and the bridle path) which gently channels runoff rainwater in two directions away from the green and bunkers. The channel is clearly visible in the first image on this page.

Gus Hook read books on grasses and soils. He joined the Middle Atlantic Greenkeepers Association and attended its meetings. He consulted golf-course superintendents all over the area, and relied heavily on the particular expertise of Bob Scott of the Baltimore Country Club. Ned Hanlon assigned engineer Charles B. Wolf to assist Hook with technical work.

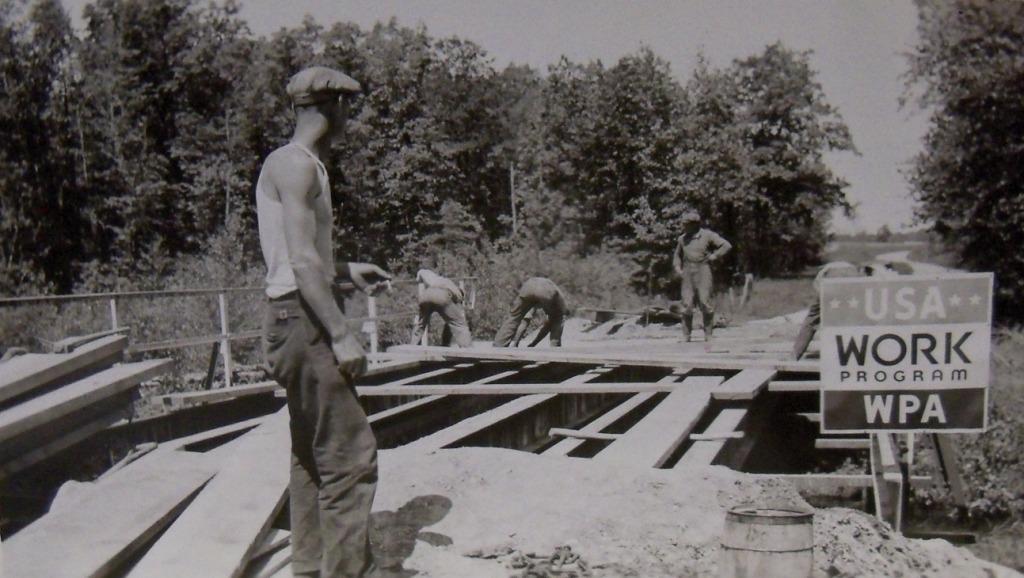

Construction resumed under Hook’s supervision in the fall of 1932. The stock market crash of 1929 had plunged the country and most of the Western world into the Great Depression and social chaos. The ability to pay for manufactured goods, and thus the demand, dropped 85% in a period of weeks, leading to a series of layoffs that put more than half of the world’s workforce out of jobs.

In the United States, President Hoover was voted out of office, and Roosevelt assumed executive control of a country near anarchy. World War I veterans, feeling ignored and unappreciated after risking their lives a decade earlier, organized and marched in a show of menace on the nation’s capitol. The Communist Party of America enjoyed a huge increase in membership. Fortunately for the collective soul of mankind, Roosevelt was a better man than his soon-to-be adversary in Europe, Adolf Hitler. Both men well understood the significance of idle hands. Hitler put them to work in his own vile service. Roosevelt created work that, although menial, required neither suppression of conscience nor abandonment of reason.

Congress created the Federal Emergency Relief Administration in early 1933. Pursuant to the authority granted by this statute, Roosevelt created through executive orders a series of programs designed to provide jobs for millions of unemployed workers. These programs included the Works Progress Administration, Civil Works Administration, Civilian Conservation Corps, Work Project Administration, and other similar initiatives. The act appropriated $500 million from the federal treasury for distribution to the states, to be used for reforestation, road construction, soil erosion and flood control, and development of national, state and local parks.

Hook and Hanlon negotiated a grant under a combination of these programs by which the manual labor costs of finishing the course would be borne by the federal government. The contract specified that tools no larger than picks, shovels, and wheelbarrows could be used on the job, to ensure that the maximum number of men would be needed to do the work. During construction, as many as seven hundred men per day were employed.

On a crowded public golf course, it is necessary to get the golfers away fast; a short hole has a tendency to clog things up on the tee. (note) The first hole had been laid out by Winton to measure 460 yards, and played as a par-five. Hook built it this way. [In 1936 the Park Board voted to make it a more difficult hole by increasing its length by moving the tee back. A 1937 newspaper article lists the hole at 530 yards. In 1975, a course map gives its yardage at 604. The 2003 scorecard makes it 565 yards.]

The second, likewise, should be a good, long hole that continues to give the golfers a chance to spread themselves thin. Hook again followed Winton’s design. The second hole’s tee box was originally placed to the west of the first green. The construction of Northern Parkway (note) forced the tee to be relocated to the present [2004] position north of the road. The hole designed by Winton and built by Hook played as a 442-yard, straightaway par-four, and is now a 347-yard dogleg right. A 1939 map of the course shows a bridle path meandering through the course. The path runs from behind the second tee in a more-or-less straight line past [and north of] the first green, passing south of the eighth green, then down the hill to pass south then east of the sixth green, and off into the woods by Herring Run.

Winton’s design for the third hole called for a par-three on what is now the seventh hole. Hook scrapped that plan, and cut the third hole through the woods along the northern boundary of the property, taking out 250 trees and piping a stream under the fairway to achieve the layout he wanted.

#3 fairway and bunkers protecting green. (Click to expand.)

#3 fairway and bunkers protecting green. (Click to expand.)

The fourth and fifth holes fell into place naturally for Hook, but No. 6 required some thought. He felt it was time for a par-three hole, but the stream that flowed through the area was not wide enough to constitute a good hazard. Hook modeled this hole after the seventeenth hole at [the 1932] Hillendale Country Club. He built a series of stone dams, creating three ponds that would catch tee shots short of the four bunkers guarding the green.

The sixth green also presented a problem. The land allowed a maximum length for the hole of 130 yards, with golfers hitting down over the ponds from the highly elevated tee. A shot hitting the green will rip out a chunk of turf. If the green is made too large, so as to spread out the damage, it would be too easy to hit with a tee shot. If the green is made too small, the shots that hit it will quickly tear it up. Hook conceived the idea of a heart-shaped green, with two distinct sides. This configuration would allow the alternation of hole locations, with one side being used for a while, then allowed to recover while the other was used. When both sides became worn, the hole could be cut in the center portion of the green. Hook made the green area huge, 14,000 square feet, so that either half of it would provide a reasonable target from a tee no more than 130 yards away.

Facing north across #6. (Click to expand.)

Facing north across #6. (Click to expand.)

The northernmost pond on No. 6 also served as a hazard for (very) poor tee shots from No. 7. The dogleg eighth presented no problems for Hook. Thomas Winton’s design for No. 9 was retained. It appears that Mr. Hook chose to respect the safety of those who used the bridle path that traversed the course. (note) No part of the course fell within an area bounded by lines connecting edges of these successive points; second tee, eighth green, sixth green, eleventh tee, tenth green, first green, and back to the second tee, and it is within this area that the path crossed the golf course. Shots [in play] were never required over the path. Maps show that this is by far the largest contiguous area that was not used in the layout of the course on the property.

Hook wanted the tenth to be a long par-five, in the event a crossover start was used, and for this hole he used the eleventh hole at Sherwood Forest Country Club as a model. In building this hole, he found it again necessary to pipe a stream under the fairway.

There was only a narrow strip of land usable for the eleventh and twelfth holes, bounded on the east by Herring Run. Hook made No. 11 a par-three and the twelfth a par-four. He overcame the narrowness of the strip by having the golfers hit out toward the green on No. 11, and into a severely sloping fairway on No. 12. The fifth hole at Rolling Road Golf Club was Hook’s model for No. 12.

A natural dogleg, the thirteenth hole was laid out along the lay of the land, and required minimal moving of earth.

Hook found the fourteenth almost impossible under the original conditions. A two-and-a-half acre parcel [reported in one place as one-and-a-half acres] of land jutting into the course boundaries forced a par-four there with much too long a walk from the thirteenth green to the fourteenth tee. A Baltimore Sun article of June 10, 1934, gives that distance as 150 yards, and reports that golfers named the walk after the owner. This property was eventually purchased from Dr. Henry B. Jacobs. A 1934 scorecard indicates No. 14 was then a 483-yard par-five. A map on the reverse of the 1957 Eastern Invitation Open pairing sheets depicts the course layout. That year, the hole played as a 525-yard, dogleg-left, par-five, indicating that the purchase of Dr. Jacobs’s land, and the subsequent lengthening of the hole, took place between those years.

When Perring Parkway was built, a big chunk of course property was taken, forcing a redesign of the 14th and 15th holes. The fourteenth hole, originally laid out west of No. 15, was made to play as a par-four, east of No. 15. The fourteenth hole originally played north-to-south, and now plays south-to-north, and the fifteenth hole plays south-to-north. Gus Hook designed the remake of the holes.

The 1932 fifteenth hole was a dogleg-right par-four measuring 447 yards, modeled after the design of the tenth hole at Five Farms. The fifteenth tee appears to have been approximately 30 yards east of where the fourteenth green was then located. Stuart B. McIver, in a Baltimore Sun article of September 15, 1952, describes the hole:

"The fifteenth, which starts just north of Woodbourne avenue, in Hamilton, is a scenic hole, some consolation for the golfer who goes for that sort of thing. Chinquapin Run splashes across the fairway in front of the green, while Herring Run flows down the east side, paralleling the fairway, ever ready to dampen a slice that strays its way. Trees grow in abundance near the confluence of the two streams, further complicating the picture for the golfer. A well-placed tee shot down the left side of the fairway is necessary, while a wood or long iron, straight and strong, is needed for the second shot. If the golfer tops or falls short, Chinquapin Run will claim him. If he hooks, the trees will get him. If he slices, he can expect either trees or Herring Run. The fifteenth is a lulu."

In 1932, the fifteenth green was located near the current [2004] tees of the fourteenth hole. Prior to the beginning of construction, Herring Run and Chinquapin Run came together at that spot. Hook built bulkheads and moved massive amounts of earth for fill (as per the contract that allowed tools no bigger than picks, shovels and wheelbarrows), forcing Chinquapin Run’s flow from an easterly direction to a southeasterly direction and Herring Run’s direction a distance to the east, and causing the two streams to meet at a point about 75 yards south and 50 yards east of the natural confluence. After holing out, golfers then walked between the thirteenth green and the fourteenth tee to the tee box of No. 16.

Hook described the sixteenth hole as “the most natural hole on the course. We didn’t even have to plow up the fairway.”

In building No. 17, Hook had to dismantle a water main and supporting trestle he himself had built when he worked for the Bureau of Water Supply. The pipe was re-laid deep underground. The approach and green were carved from the steep hill that sloped down from the mansion. A 1932 photograph of the hole shows a gentler slope left of the green, and no bunkers. It appears that the bunkers were added sometime after the original construction. A 1939 course map shows the bunkers had not yet been added.

This photo's hard to date. There's no cart path on #18, no stairway

up to #17 green, and the cart path straight down the hill from #17 tee appears intact. The trees between the cart barn and roadway are young. The Starter Shack also

appears in a different place. (Click to expand.)

This photo's hard to date. There's no cart path on #18, no stairway

up to #17 green, and the cart path straight down the hill from #17 tee appears intact. The trees between the cart barn and roadway are young. The Starter Shack also

appears in a different place. (Click to expand.)

The last hole was designed, in the confines of the remaining land, as an uphill dogleg left measuring 346 yards. The hole offers the option to cut the dogleg and fire directly at the green by carrying the last 40 yards over an out-of-bounds area having several tall [and growing] trees. Hook’s design required a carry of 243 yards. In 1998, Rick Hudak cut a new tee box out of the hill behind the original tee, and that tee increased the required carry by 30 yards.

When completed in 1934, the course featured 57 bunkers, 32 on the front and 29 on the back nine, almost all of them protecting the greens. Par was 72. Total distance was 6,753 yards from the back tees.

Hook’s greens, except the sixth, averaged 9,000 square feet in area. For a public course in 1934, these were quite large. The greens at Clifton Park Golf Course, for example, averaged 4,500 square feet. For purposes of comparison, if the greens were assumed to be perfect circles, the distance from the center to any point on the edge of a 4,500 square-foot green would be 39 feet, and 54 feet on a 9,000 square-foot green, and the green depths would be 26 yards and 36 yards, respectively.

All the greens were piped for water, but not the fairways or tees. Hook also spaced six water fountains around the course for the refreshment of golfers, caddies, and spectators.