Edward Hugh (Ned) Hanlon | Mount Pleasant ParkGolf CourseMaryland's Tournament CourseEstd. June 30, 1934 | Charles Augustin (Gus) Hook |

Edward Hugh (Ned) Hanlon | Mount Pleasant ParkGolf CourseMaryland's Tournament CourseEstd. June 30, 1934 | Charles Augustin (Gus) Hook |

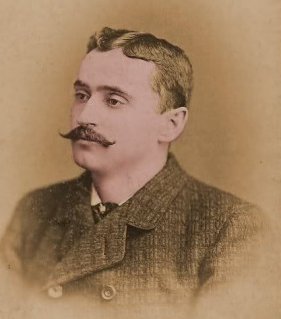

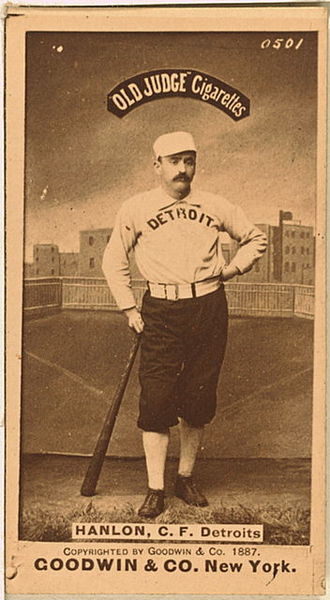

Edward Hugh (Ned) Hanlon (1857–1937) (note) weighed 170 pounds. He batted left-handed and threw with his right. He played 13 seasons as an outfielder in the major leagues, most with the Detroit Wolverines, and hit .260 over those years. He finished his playing career with the Baltimore Orioles in 1892, and the next year became the team’s manager.

The owner of the Baltimore Orioles was Harry von der Horst, who was also a minority shareholder in the Eagle Brewery, one of 60-some breweries located in Baltimore at the time. The majority stockholder in the Eagle Brewery was its founder, and Harry's father, John von der Horst. The brewery was located on Belair Avenue (now the 900 block of Gay Street). Harry had purchased a baseball franchise in the American Association in 1881 for $50 and named the new team the Orioles.

The younger von der Horst had a good idea. His main business was selling beer. If he owned a baseballl team, he could sell beer to fans attending the games. By 1892 he had learned that the better his baseball team, the more fans that attended the games, and the more beer he sold. His teams in previous years had not performed well, and he was a little short on capital. He struck a deal with Ned Hanlon: Hanlon would invest some of his savings in the club in return for minority ownership and the right to run it as he saw fit.

Hanlon’s accomplishments as a manager far exceeded his exploits as a player. He had a fiery and raucous temperament, and this attitude rubbed off on his players. His ball clubs were aggressive, and made up in spirit what they lacked in talent. Hanlon used what tools he had to win games. He is credited with being the first to have his teams practice the skills used in playing the game, at the time an unheard-of exercise.

The Orioles were a weak-hitting club. To aid his offense in scoring runs, Hanlon devised or perfected the techniques of the suicide-squeeze bunt, the hit-and-run play, and the Baltimore Chop. He instructed his groundskeeper to insure that the infield foul-lines sloped towards fair territory, so that bunts wouldn’t roll foul. The groundskeeper was also forbidden to water the ground and grass around home plate, resulting in the area becoming packed hard, the better to bounce bunts and Baltimore Chops higher in the air, giving Hanlon’s runners advantages over opposing fielders. Hanlon even went so far as to slope the basepath from home to first downhill so that his runners had a split-second advantage over infielders fielding grounders and throwing to first. Under Hanlon, the Baltimore Orioles won pennants in three successive years, 1894 through 1896. (note)

Hanlon had an autocratic nature. He felt that, if given a job to do to, he should be free to do it without interference, and without having to explain what he was doing. His majority partner in the Orioles, Henry von der Horst soon learned this facet of Hanlon’s disposition. When he faced the press to answer questions about his ball club, von der Horst took to wearing a lapel button that read, “Ask Hanlon.” Hanlon’s knowledge of baseball and how the game should be played were acknowledged and respected by the team owners. After he retired as a manager, he was hired to head major league baseball’s Rules Committee.

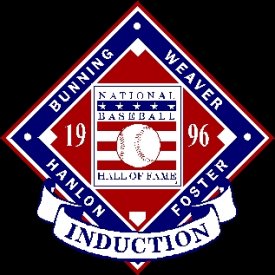

Ned Hanlon was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1996. Six men who played for Hanlon are also enshrined in the Hall. They are Miller Huggins, John McGraw, Joe Kelley, Dan Brouthers, Hughie Jennings, and Wilbert Robinson. A seventh who played for Hanlon, William J. “Kid” Gleason, might have joined them in the Hall of Fame. Gleason won a pennant in his first year as a major-league manager, but unfortunately, the team he managed was the 1919 Chicago White Sox.

In 1916, Hanlon was appointed to the Baltimore Park Board by Mayor James H. Preston. At age 73, he became its president in June, 1931. When it became apparent that the Mount Pleasant Park project was to be a failure, Hanlon began his search for a superintendent capable of finishing the job.

Charles Augustin (Gus) Hook was born in 1898. In 1913, he went to work with the Forestry Division of Baltimore City. Part of the time he was a high-tree climber, clambering up tall trees in the parks in order to cut off dead limbs. In World War I, Hook enlisted in the Army. He was shot in battle in the Argonne Forest in France, and was awarded the Purple Heart. (note) The bullet that wounded him could not be surgically removed, and remained in Hook’s arm for the rest of his life. After his discharge, Hook returned to Baltimore and took a job with the city's Bureau of Water Supply, where he worked for 10 years. About 1930, he earned the highest mark on the City Service Commission exam, and was therefore promoted to superintendent of the Patterson Park District. He would move up to become superintendent of the Clifton District in 1932, and then chief superintendent of all the city parks.

Gus Hook was an accomplished amateur golfer. Three times between 1922 and 1933 he played on teams representing Baltimore City in the U.S. Amateur Public Links Team Championship. He eventually joined Hillendale Country Club.

The Purple Heart

The Purple HeartGus Hook and Ned Hanlon met on the grounds of Mount Pleasant Park soon after work was halted in June, 1931. Ned Hanlon was the 73-year-old, newly-installed president of the Park Board, the father of a soldier who had been shot and killed in France in W.W.I. Gus Hook, age 33, still carrying a bullet in his body from the same war (maybe even the same campaign—the Battle of the Argonne Forest was the deadliest in American history), almost certainly had been installed in the position of superintendent of the Patterson Park District. Hanlon outlined his requirements: an 18-hole, state-of-the-art, championship golf course that would provide a stern test for the best golfers.

“Can it be done?” he asked.

Hook asked for a few days before giving his answer. During those days he walked the property many times; sometimes hitting real golf shots and other times visualizing shots in his mind. He studied the model Thomas Winton had constructed. He measured distances, angles, and elevations, and calculated the number of trees that would have to be cut down. He noted the location of the several streams that traversed the lot, and realized that they would have to be rerouted. The parcel of land that had been acquired by the city consisted of 260 acres. However, Hillen Road cut through the property, effectively slicing off 80 acres from use, leaving only 180 acres on which to put 18 holes and the required buildings. Gus Hook determined that a course could be built to the required standard. He informed Hanlon that it could be done, and that he could do it.

Ned Hanlon shook his hand and said, “You’re my boy!”