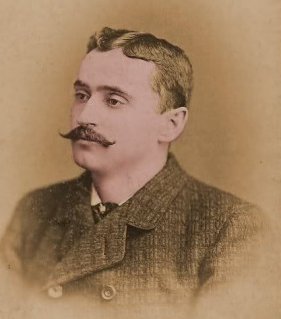

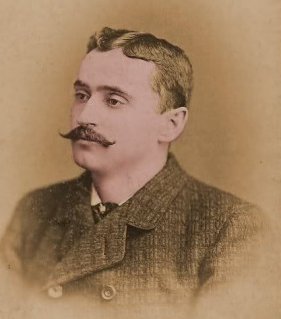

Edward Hugh (Ned) Hanlon | Mount Pleasant ParkGolf CourseMaryland's Tournament CourseEstd. June 30, 1934 | Charles Augustin (Gus) Hook |

Edward Hugh (Ned) Hanlon | Mount Pleasant ParkGolf CourseMaryland's Tournament CourseEstd. June 30, 1934 | Charles Augustin (Gus) Hook |

On May 9, 1950, the Baltimore Park Board held an interesting meeting.

Memorial Stadium in 1950.

Memorial Stadium in 1950.

Jack Dunn, III, owner and president of the [minor league] Baltimore Orioles Baseball Club (note), asked the Board to renegotiate the contract between his team and the city. Dunn reported that the Orioles had suffered a corporate revenue loss of $200,000 over the previous two years, and that, unless the city made certain concessions, the franchise might be forced to move from Memorial Stadium to a new location. The city had borne the costs of construction of the stadium in 1949, for the use of the Orioles and college football teams that wanted to lease it. The Board, after consideration, agreed to Dunn's demands that the city assume the costs of cleaning the stadium after baseball games, and to erect fences and chains to help in controlling fans. Dunn agreed to continue to pay the city as rent seven cents per spectator. It is not known if representatives of other ball clubs were present, taking notes on what would become the epitome of municipal blackmail by sports franchises. (note)

Dr. Bernard Harris, the only black member of the Park Board, proposed an end to segregation at Carroll Park Golf Course. At the time, Tuesdays and Wednesdays of each week were reserved only for white people to play the course, and on the other five days per week only black people were allowed to play. Dr. Harris suggested that the Board abolish this rule, and allow any golfer to play whenever he chose, as “an experiment” to determine “the attitudes of golfers.” In opposition to this proposal, Dr. J. Ben Robinson pointed out that to end segregation at one course, and not at others, would be “inconsistent.” Dr. Harris’s proposal was defeated, the proponent and S. Lawrence Hammerman voting in favor, while Robert Garrett, the board president, Dr. Robinson, and George G. Shriver voted to maintain the desired "consistency." (note)

In June, 1942, Mount Pleasant Park Starter William H. Tudor

refused to allow African-American golfers to play on the course. One of those refused was noted civil-rights attorney

Dallas Nicholas, who was the lead lawyer in the case against the Park Board that held, in 1951, that its discrimination based on race was unconstitutional.

In June, 1942, Mount Pleasant Park Starter William H. Tudor

refused to allow African-American golfers to play on the course. One of those refused was noted civil-rights attorney

Dallas Nicholas, who was the lead lawyer in the case against the Park Board that held, in 1951, that its discrimination based on race was unconstitutional.

The Board voted unanimously in favor of the next item. The Eastern Invitation Open was approved to be held at Mount Pleasant Park in August of 1950. Thomas J. O’Donnell, the city public relations director and tournament chairman, reported that profits from the event would be used for the benefit of the Baltimore Zoo. (note) The Gunther Brewing Company contracted to put up the purse of $16,500 in return for radio and television rights to the event. (note) [Presumably, television rights were limited to the later broadcasts of film of the tournament. The first live network telecast of a golf tournament would take place in Chicago in 1953, at the Tam O’Shanter World Championship. In 1954, the U.S. Open Championship was televised live for the first time.]

Expenses to be incurred by the course, estimated at $5,000, would be reimbursed from admissions fees. O’Donnell told the board that the tournament was expected to be an annual event, and that he had applied for a copyright on the name. He further explained that the tournament would offer the third highest amount of prize money on the tournament circuit in 1950, behind only George S. May’s Tam O’Shanter World Championship in Chicago and the PGA Championship.

Lloyd Mangrum won the first Eastern Invitation Open at Mount Pleasant Park Golf Course, deeming it “the finest public course I’ve ever seen or played on.” Mangrum shot 279, bettering par by nine strokes to win the first-prize check of $2,600, his largest payday of the year. [Mangrum had collected $2,500 for losing a playoff to Ben Hogan in the U.S. Open Championship at Merion Cricket Club in Ardmore, Pennsylvania, a few months earlier.] The course had been set up to keep scores high, as only Mangrum [69], Orville Wright [69], of Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and Andy Gibson [71], Country Club of Maryland, broke par on the final day.

Frank Michalek, of the host course, won low-amateur honors with a five-over-par 293. Ralph Bogart, of Chevy Chase, was second low-amateur, at 297. Walter Romans (note), of the Baltimore Country Club, finished in a tie with Freddie Haas for seventh place at 286, and captured the low-Maryland-professional honor.

The event turned a modest profit, which was given as promised to the Baltimore Zoo. Attendance at the clinics put on by the professionals, at the practice rounds, and at the tournament proper exceeded 25,000, including 10,000 who watched the professionals on Sunday.

The Eastern Invitation Open did become an annual event, as tournament director Thomas J. O’Donnell had envisioned. It was played at Mount Pleasant each year up to 1958 with various civic-minded companies sponsoring the event.

The tournament became profitable, and the excess money realized by the Park Board was used to create a new golf course, Pine Ridge, in the woodland watershed of Loch Raven Reservoir north of Baltimore City. Ironically, it was to Pine Ridge that the tournament shifted in 1959. Gus Hook said to the Baltimore Board of Estimates about the change of location, “Many people have asked me why we don’t move to Pine Ridge, and we think they are right.” The reasons given by the Park Board for the move were that Pine Ridge would attract a larger crowd and thus produce a bigger gate, and that construction on the clubhouse at Mount Pleasant and on roads surrounding the course would interfere with the tournament.

Pine Ridge Golf Course (click to expand)

Pine Ridge Golf Course (click to expand)

Ironically also, Gus Hook was the designer of Pine Ridge Golf Course. His son, Dr. John Randolph Hook, fondly recalls riding with his dad in a Jeep over the course grounds while construction was in progress. Hook explained to his son that his design allowed a view of the water from at least one spot on every hole.

Pine Ridge Golf Course opened in April, 1959, and the tournament was held there in June. PGA officials permitted the competitors to play an early version of lift-clean-and-place. Because of the sparseness of the newly-grown grass, they were allowed to nudge their balls in fairways with their clubheads. It was immediately apparent that, although Pine Ridge was a beautiful course, it was not the test for expert players that Mount Pleasant had been. Dave Ragan won the tournament with a score of 273, lowering the Eastern Invitation Open record set by Sam Snead in 1952 by two strokes. The tournament paid the top 33 finishers that year, and all finished with sub-par scores. The trend continued in 1960, with the top 36 finishers receiving checks, and all were under par. The top 34 in 1961 finished under par. Forty-four spots were paid, with the last five golfers earning checks in a tie at one-over-par 289.

The tournament returned to Mount Pleasant in 1962. Scores were predictably higher. Doug Ford won with a score of 279, beating Bob Goalby by a stroke and Champagne Tony Lema by two. Fourteen golfers finished under par, and ties for fortieth place earned the last payoffs of $164.44 at four-over-par 292.

In the inaugural tournament in 1950, a Mount Pleasant Park course record of 65 was set by Clayton Haefner in the first round. The second round saw another course record set, a score of 100 by Bob Crow, a professional from Bethesda, Maryland. Mr. Crow’s record was never exceeded in Eastern Open competition. Mr. Haefner’s record 65 was equaled once, by Dow Finsterwald in 1958, and lowered by a stroke to 64 in 1957 by Tommy Bolt. Rounds of 66 were recorded by Doug Ford [1952], Ralph Lomeli [1953], Bob Toski [1954], Arnold Palmer [1956], and Fred Hawkins [1957].

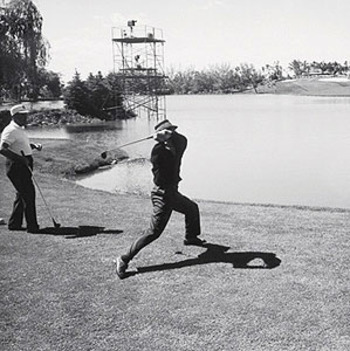

"Terrible" Tommy Bolt was the greatest club-thrower in PGA history. Through the bag, putter to driver, Bolt could launch them all. No one-trick-pony, Bolt could throw

clubs both on land and into water, first hole or last, right-handed, lefty or (as documented above) with both. He was also known as the go-to-guy for bad-tempered rookies, always approachable for advice on

throwing: distance, direction, form, and even his trademark move, helicoptering. He also won a U. S. Open.

"Terrible" Tommy Bolt was the greatest club-thrower in PGA history. Through the bag, putter to driver, Bolt could launch them all. No one-trick-pony, Bolt could throw

clubs both on land and into water, first hole or last, right-handed, lefty or (as documented above) with both. He was also known as the go-to-guy for bad-tempered rookies, always approachable for advice on

throwing: distance, direction, form, and even his trademark move, helicoptering. He also won a U. S. Open.

Arnold Palmer played in the Eastern Open at Mount Pleasant three times. In his first venture in 1955, he finished in 16th place with a four-round score of 290, ten strokes behind the winner, Frank Stranahan. Palmer won the tournament in 1956, shooting 277 to beat Dow Finsterwald by two shots and Bob Rosburg by three. A month earlier he had recorded his first professional triumph in the United States, winning the Insurance City Open at Wethersfield, Connecticut. In 1957, Palmer finished eighth, tied with Charlie Sifford at 283, seven shots behind the winner Tommy Bolt. He didn’t enter in 1958 or 1959.

Recounting his victory, Mr. Palmer said, “There was a very unique situation involved when I won the Eastern Open there in 1956. I hit my very first shot in the tournament out of bounds. I kinda flipped my driver up in the air in disgust when that happened. Doug Ford was playing with me that day and I said rather quietly to him: 'I think I'll just go home. I'm tired.' I remember Doug's response so well: 'Come on. You can spot the field two shots and still win the tournament.' Which I did. Although I wound up winning by two over Dow Finsterwald, I led by 12 strokes at one point in the tournament."

J. Harold Grady

In 1959, Irv Kovens’s hand-picked candidate, J. Harold Grady, the State’s Attorney for Baltimore City, defeated the incumbent mayor of Baltimore, Thomas J. D’Alesandro, Jr. [father of Nancy Pelosi, former Speaker of the U. S. House of Representatives] in the viciously-contested Democratic mayoral primary election. In the general election, Grady won over Theodore McKeldin, a former mayor of Baltimore and the then-incumbent governor of Maryland. The victory of Kovens’s man marked the end of James H. “Jack” Pollack’s power as a kingmaker, Pollack having backed Mayor D’Alesandro in the primary election, and paved the way for Kovens to assume Pollack’s power. “To the victor belong the spoils.” Part of the spoils in the city of Baltimore was the general chairmanship of the Eastern Invitation Open, to which position Mr. Kovens was appointed by Mayor Grady upon the latter’s assumption of office.

[Pollack wasn't dead yet. He discovered that there was this thing in Baltimore City that called itself 'The Republican Party.' Although barely alive, this organization nevertheless had the right to put up candidates in a general election, and ran primary elections that were won by city-wide candidates who marshaled hundreds (as in, not even thousands) of votes. Pollack energized his former cronies and underlings. They registered as Republicans, and backed McKeldin, who ran again for mayor in 1963. He, and Pollack, won. For an excellent thumbnail sketch of 20th century Baltimore politics, see Mark Bowden's 1979 City Paper article titled "Bossing' Around."]

Governor McKeldin signs a bill in 1956. Irv Kovens is in his usual spot, at the center of power but hovering in the background. He

is standing behind the woman on the left, and close to the American flag.

Governor McKeldin signs a bill in 1956. Irv Kovens is in his usual spot, at the center of power but hovering in the background. He

is standing behind the woman on the left, and close to the American flag.

As general chairman of the tournament in 1960, Kovens complained to PGA officials that Sam Snead and Arnold Palmer were playing an exhibition match in Pennsylvania, in violation of the contract the Eastern Open had with the PGA that forbade such matches within 200 miles of the Eastern Open site during play of the tournament. Bob Rosburg, chairman of the PGA tournament committee, promised action that would mollify or compensate the tournament. However, further investigation revealed that Kovens himself had had an undisclosed agreement with Snead, in violation of the contract, whereby Snead was paid an appearance fee of $500 to play in the Eastern Invitation Open pro-am, and that Kovens had offered an under-the-table payment of $1,000 to Palmer, likewise in violation of contract, to play in the tournament proper. Snead beat Palmer in an exhibition match before 3,000 fans at Lulu Temple Golf Course near Philadelphia as Gene Littler held off Gary Player’s charge to win the 1960 Eastern Invitation Open. Littler won $3,500, and Player collected second-place money of $2,300. The amounts of the fees paid to Snead and Palmer for playing the exhibition match were not disclosed, but they needn’t have been much higher than what Kovens had offered in order to make the financial incentive greater to play the exhibition match for a sure payoff than to compete in the tournament. Kovens and the Eastern Invitation Open received no compensation from the PGA of America for the alleged breach of the contract.

The name of the tournament, the Eastern Invitation Open, had its genesis in the complex racial politics of the era. Professional golf, much like major league baseball and other sports, had adopted exclusionary policies and practices that effectively kept blacks from competing with whites for the highest purses. The following article, written by Al Barkow, Golfweb columnist and former editor-in-chief of Golf Magazine, explains the reason for the awkward and apparently self-contradictory name:

"In the long and torturous history of race relations in the United States, one of the most blatant racist acts by an established national organization was the clause that restricted membership in the PGA of America only to Caucasians.

"The Caucasians-Only clause was written into the organization's constitution in 1943. The amendment read: "Professional golfers of the Caucasian race, over the age of eighteen years, residing in North or South America, and who have served at least five years in the profession (either in the capacity of a professional or in the employ of a professional as his assistant) shall be eligible for membership.

"Before the Caucasians-only clause was rescinded, one black professional did become a member of the association. But his inclusion came by accident, and when the mistake was discovered he was summarily removed from the roles.

"This was the case of Dewey Brown, who began in golf as a caddie and eventually became a skilled player and clubmaker who taught the swing and made clubs for everyone from wealthy businessmen to a U.S. President (Warren G. Harding). In 1928, his application for membership in the PGA of America was accepted, presumably because, being a light-skinned Negro, he was mistaken as a white man. In 1934, the PGA discovered his true heritage and withdrew his eligibility without explanation.

"No one has ever made clear what prompted the 1943 inclusion of the Caucasians-Only clause in the PGA's charter. According to one piece of conventional history, the clause came about when a white woman professional sought to join the PGA. How that led to the exclusion of people of color is difficult, if not impossible, to comprehend. The fact that it was promoted by the Michigan section of the PGA of America offers a more logical clue. The historian of the PGA of America, Herb Graffis, said the action was stimulated by a concern that those already belonging to the association -- all of them white, of course -- were having trouble finding jobs due to the ongoing World War II. The clause was meant to keep them employed, or get them re-employed in a job-scarce field.

"Over the next few years, some state PGA sections proposed removing it, including the Michigan group. But these efforts were blocked, usually by PGA sections in the southern tier. In one instance, a defense of The Clause by a PGA delegate went as follows: "Show us some good golf clubs Negroes have established, and we can talk this over again." But what did owning or establishing a golf club have to do with becoming a working golf professional and a member of the PGA? Besides, while there had been in fact one or two golf clubs formed by blacks, by and large African-Americans could only play public courses, and in almost every case only city-owned munis in the north. Those generally were open to them on a restricted basis -- on certain days, or at certain hours. Separate but unequal ruled, as it still did in other areas of American society.

"It was a controversial amendment, but not much was done about it until 1948. That was one year after Jackie Robinson became the first black to play major league baseball, as well as when President Harry Truman issued an executive order desegregating the U.S. Armed Forces. Both were undoubtedly inspirations for black golfers to try breaking down the racial barriers in golf. The main man in that quest was Bill Spiller.

"Spiller was born in Oklahoma and earned a degree in education and sociology from Wiley College, an all-black school in Texas (where a future Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall, also attended). Unable to obtain a decent paying job as a teacher, he moved to Los Angeles and became a redcap in Los Angeles' central railroad terminal. He also took up golf, and being a good athlete (he ran track at Wiley), Spiller soon became one of the better black golfers in the country, along with Ted Rhodes, Howard Wheeler and others who proved themselves on a black professional tournament circuit that had been developed. Only three sponsors of PGA tournaments allowed blacks to play and compete against whites. They were the Canadian Open, the Tam O'Shanter All-American and "World" in Chicago and the Los Angeles Open. Blacks could not play in the other tournaments, because they were not members of the PGA of America, which at the time was running the circuit. It was the Los Angeles Open that, unwittingly, became the catalyst for eventual change.

"A stipulation in the PGA's rules said that anyone who finished in the top 60 of a tournament was automatically qualified for the field for the next event on the schedule. Rhodes and Spiller finished 21st and 34th, respectively, in the 1948 Los Angeles Open and traveled north to play the next week in the Richmond Open, outside Oakland. After their second practice round, George Schneiter, the PGA's tournament manager (who also competed), told Rhodes, Spiller and Madison Gunther, another black player who had qualified locally, that they couldn't tee it up in the Richmond event because they were not members of the PGA of America. That requirement superseded the top-60 condition, he said.

"Spiller was enraged. Through an old college friend, he connected with a black attorney, Jonathan Rowell, who had some experience in racial discrimination cases–although not much, as it turned out. A suit was filed against the PGA of America by Spiller, Rhodes and Gunter for $315,000 on the grounds they were denied the opportunity to obtain employment in their chosen profession. Since the late 1930s, at least, there had been a number of suits filed by blacks against public golf courses that denied them access but nothing had gotten the attention this suit did. Along with newspaper coverage, the issue was also propelled by the fledgling ABC Radio Network, which had been informed of the incident by Spiller's friend.

"When push came to shove, however, Rowell was gulled by the PGA's attorney. Before the case went to court, Rowell was told that if the suit was dropped the PGA would in the future rescind the rule barring blacks. And, blacks would not be refused playing privileges in events designated as opens, as most were at the time. Rowell convinced Spiller, et al to drop the litigation. Then, the PGA and most of its sponsors began designating its tournaments as Invitationals, or Open Invitationals. Of course, no blacks got invited. End of story, until 1952.

"That year, Spiller and Rhodes were invited to try qualifying for the San Diego Open, which at the time was thought to be purely a charity event and not under PGA auspices. They qualified, and were joined by Joe Louis, the heavyweight champion, who had been invited to play as an amateur. But then, PGA of America president Horton Smith, winner of the first and third Masters tournaments, stepped in and said Spiller, Rhodes and Louis could not play as they were not members of the association. Louis called the highly popular, nationally syndicated newspaper columnist Walter Winchell, who also had a radio program every Sunday evening. Winchell let Mr. and Mrs. America and all the ships at sea -- his opening line, punctuated by a Morse Code ticker in the background -- that the great boxer who had served his country in the military (and in the ring badly defeated Hitler's Max Schmeling) had every right to compete in a golf tournament. As did other blacks.

"Smith called a meeting two days before the tournament in San Diego was to begin. Louis, two of his black friends, Leonard Reed and Euell Clark, and Rhodes were invited to attend. Spiller, who was known to be outspoken, was not. But Spiller was encouraged by Jimmy Demaret to go ahead and go to the meeting. He did, and he and Smith went toe-to-toe, head-to-head. Spiller not only wanted the PGA to allow blacks to play on the tour, he also sought membership in the PGA of America so he could, possibly, find a good club job. Smith did not relent, and Spiller again threatened a lawsuit. At that point, Jackie Burke and Leland Gibson, two tour players -- Burke won a PGA Championship and Masters -- told Spiller to hold off and give them a chance to work something out. Spiller said he would, but added, "If you don't, I'll see you in court. You ran over me the last time, but you won't this time."

"As it happened, Joe Louis did play in San Diego. Spiller and Rhodes did not, but the PGA added an amendment to its constitution by which non-members could compete in tour events as "Approved Entries" if they received invitations from sponsors. This time, some sponsors came through. Spiller and Rhodes played in Phoenix and Tucson in the two weeks after the San Diego confrontation and in 10 more tournaments that year -- all of them in the Midwest and east. The way was clear, more or less, for Charlie Sifford to begin playing most of the circuit. Spiller, who was getting up in Charlie Sifford years, played a limited schedule, as did Rhodes, whose health was beginning to decline. At that, The Clause was still intact and remained so until 1962, when the issue came to a final head.

"Here again, Spiller was in vanguard. He had been caddying around Los Angeles to make some extra money, and one day looped at the Hillcrest Country Club for a man named Harry Braverman. Braverman knew of Spiller's ability to play golf, and asked him why he was out there packing bags for others. Spiller told Braverman of the struggle that blacks had been waging and about The Clause. Braverman advised Spiller to write a letter explaining the whole matter to the California Attorney General, Stanley Mosk. He did, and Mosk -- who had also heard of the matter from Maggie Hathaway, a black activist in Los Angeles, and Sifford -- told the PGA of America it could no longer play any of its tournaments in California on public courses if blacks were not allowed to participate. The PGA said it would play on private club courses, instead, but Mosk told them he would not allow that to happen, either. What's more, Mosk wrote attorney generals of most of the other states to tell them of his action and urged they do same.

"The publicity the PGA of America was getting was increasingly negative, so in November, 1961, at the association's annual meeting, The Clause was voted out of the constitution. Quietly. It received only a brief mention in the PGA's house organ. But it was gone, and the way was open for Sifford to play the circuit full-time, followed by, among others, Pete Brown, Lee Elder, Jim Dent, Calvin Peete, and finally, Tiger Woods."

Read the story of the integration of Baltimore City's athletic facilities and fields, if you choose. Were it fiction, and if you could get by the tediousness and interminable length of the battle, the facts simply wouldn't be believed. This excellent treatise, the doctoral thesis of Ms. Sara Patenaude for her degree at Georgia State University, won the Arnold Prize for Outstanding Writing on Baltimore's History, presented by the Baltimore City Historical Society in 2012. Read it here.

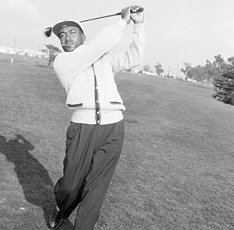

Charlie Sifford played at least ten consecutive years in the Eastern Invitation Open, from 1953 to the last year of the tournament in 1962. Presumably, he was granted admittance as an “Approved Entry,” the category in which blacks were admitted to play after Walter Winchell’s radio tirade sparked public condemnation of the PGA of America in 1952.

Ted Rhodes was another black man who, like Sifford, was just looking for a game. Rhodes competed in the 1953 Eastern Invitation Open, recording a four-round score of 297, out of the money, and 18 strokes behind the winner Dick Mayer. We also find Mr. Rhodes competing in 1958, where he again shot 297, again out of the money, this time 21 strokes behind the winner, Art Wall, who prevailed in a playoff against Bob Rosburg and Jackie Burke for the title.

The competitors in the tournament were the cream of the national crop. The only well-known golfers of the era who never competed in the Eastern Open were Ben Hogan, Jimmy Demaret and Jack Nicklaus. Hogan was lame when the Eastern Opens began, and he was playing a schedule that included major championships almost exclusively. The only Eastern Open contested after Nicklaus turned professional was the 1962 event, and Nicklaus had won the U. S. Open (in an 18-hole Sunday playoff against Arnold Palmer) just the week before. I don't know why Demaret never teed it up. The names of Baltimore- and Maryland-area amateurs and professionals abound, and almost every golfer who competed in the tournament over its 13-year history is listed in the scoring charts on the respective tournaments' pages.

| Year | Winner | Winning Score |

Purse | Winner's Share |

Winner's Percent |

Places Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | Lloyd Mangrum | 279 | 14,400 | 2,600 | 18% | 20 |

| 1951 | Cary Middlecoff | 279 | 15,000 | 2,400 | 16% | 33 |

| 1952 | Sam Snead | 275 | 15,000 | 2,400 | 16% | 34 |

| 1953 | Dick Mayer | 279 | 13,547 | 2,400 | 17.7% | 20 |

| 1954 | Bob Toski | 277 | 18,820 | 4,000 | 21.25% | 22 |

| 1955 | Frank Stranahan | 280 | 17,500 | 3,000 | 17% | 30 |

| 1956 | Arnold Palmer | 277 | 19,000 | 3,800 | 20% | 30 |

| 1957 | Tommy Bolt | 276 | 20,000 | 2,800 | 14% | 33 |

| 1958 | Art Wall | 276 | 20,000 | 2,800 | 14% | 36 |

| 1959 | Dave Ragan | 273 | 20,000 | 2,800 | 14% | 33 |

| 1960 | Gene Littler | 273 | 25,000 | 3,500 | 14% | 37 |

| 1961 | Doug Sanders | 275 | 34,400 | 5,300 | 15.4% | 44 |

| 1962 | Doug Ford | 279 | 35,000 | 5,300 | 15.1% | 40 |

The Eastern Open was contested 13 times, three times at Pine Ridge Golf Course (listed in brown above). A total of $267,667 in prize money was paid out in those years. A total of 414 spots were paid. A significant number of the professionals cashed more than once. One amateur (Deane Beman, in 1958) would have cashed (for about $150 for a tie for 27th place) had he been a professional. Adjusted for inflation, the buying power of the 13-year-total of Eastern Open prize money in 2013 is about $2,250,000. The Eastern Open paid more in prize money than most tournaments in those days, and in its early years, even paid more than the U.S. Open and the Masters. In 2013, the U.S. Open paid 69 professionals $8 million. The 2013 Masters paid 60 pros $8 million. |

||||||