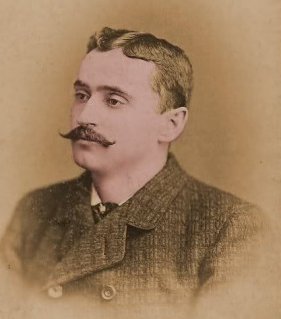

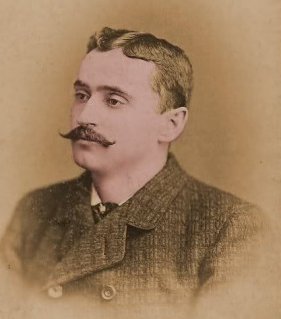

Edward Hugh (Ned) Hanlon | Mount Pleasant ParkGolf CourseMaryland's Tournament CourseEstd. June 30, 1934 | Charles Augustin (Gus) Hook |

Edward Hugh (Ned) Hanlon | Mount Pleasant ParkGolf CourseMaryland's Tournament CourseEstd. June 30, 1934 | Charles Augustin (Gus) Hook |

In 1492, Christopher Columbus anchored his ships, Nina, Pinta, and Santa Maria, off the Caribbean island of Santo Domingo, and on coming ashore, claimed it and the rest of the New World for his patrons, Ferdinand and Isabella, the king and queen of Spain.

Henry VII, King of England, worried that God might be allowing rival monarchs to grab more stuff than he, quickly dispatched John Cabot, an Italian explorer, on a westward expedition. Cabot sailed to North America where he planted the flag of the British Empire on behalf of Henry. Not wanting to be shut out, the French then sent Giovanni de Verrazano. Amerigo Vespucci followed, representing the Italians. Each laid claim to the continent for their respective sovereigns.

As there was no forum in which these competing claims could be adjudicated and enforced, ownership of the land and profit therefrom would come to be determined on the honored ancient principle dictating that might makes right. The parties adopted various strategies in hopes of prevailing in the struggle for domination in the newly discovered land. The Spanish chose the historically-proven tactic of savage-and-pillage, smashing the Native American civilizations in what is now Mexico and sending the confiscated loot to the home country as plunder. The French established ostensibly friendly relations with the native tribes inhabiting what are now the United States and Canada, and by means of incentives and bribes incited them to make constant war on the enemies of the French. The Italians essentially dropped out of the contest. The English took the long view, understanding that a large number of colonists with allegiance to the crown would ultimately establish the might necessary to protect and maintain a distant possession.

This land was home to nothing but happy Indians and herds of buffalo. Then the Palefaces came. (Click image to expand.)

This land was home to nothing but happy Indians and herds of buffalo. Then the Palefaces came. (Click image to expand.)

George Calvert, the first Baron Baltimore, was born in Kipling, County Yorkshire, England, about 1582, and died in London in 1632. He was graduated at Oxford in 1597, then sent abroad by his family to further his education. On his return he became secretary to Robert Cecil, the Secretary of State for King James I. Cecil obtained for him a clerkship on the Privy Council. In 1617 he was knighted by King James, thus becoming the first Lord Baltimore.

Calvert had for some time been interested in the colonization of the New World. He was a stockholder and member of the Virginia Company, which had established settlements since 1606 along the James River in the new colony. In 1621 he obtained from the king a patent for a few hundred thousand acres in southern Newfoundland, which he named Avalon. He visited this colony in 1625, and again in 1627, but was much disappointed to find the climate so severe. In 1628 he visited Virginia and explored the Chesapeake Bay. His reception in Virginia was unfavorable, on account of his Catholic beliefs, for the Church of England had full control of the government of the state. Notwithstanding this, he was delighted with the climate of this part of the country, and persuaded the king [now Charles I, who succeeded his father in 1625] that the granting of a colony in the New World to him would be most beneficial to Charles. In 1632 the terms of a patent were negotiated, bestowing upon Lord Baltimore that part of the country between the 40th parallel and the south bank of the Potomac River. (note) Before the grant became official, George Calvert, the first Lord Baltimore, died.

The 40th parallel is a due east-west line very near the later laid-out Mason-Dixon Line. The latter forms the northern boundary of Baltimore County and part of the Maryland-Pennsylvania boundary. The south bank of the Potomac River intersects the 40th parallel (generally somewhere) around present-day Hagerstown, and winds southeastward toward Washington, D.C. It then moves south, then east, and intersects with the Chesapeake Bay. Thus the Potomac's riverbank formed the western and southern boundaries of the patent, the Mason-Dixon line was the northern boundary, and the Chesapeake Bay was the eastern boundary. Later deals with Virginia got Maryland land west of Hagerstown, and the state got the Eastern Shore from Delaware.

Cecilius (Cecil) Calvert, son of George, and thus the second Lord Baltimore, was born about 1605 and died in London in 1675. About 1623 he married Anne Arundell, after whom the county in Maryland would be named. On 20 June 1632, the charter intended for his late father was issued to him. It granted to Cecil, as the Lord Proprietor, many of the rights of a feudal sovereign, but provided for popular government and exempted the colonists from taxation. Cecil named his new domain MaryLand in honor of the king’s wife, Queen Henrietta Maria, daughter of King Henry IV of France.

In November 1633, Cecil sent an expedition under the command of his brother, Leonard Calvert, to the colony. Cecil himself never set foot on his New World land, but governed it through various deputies for 43 years.

The only son of Cecil, Charles Calvert, the third Lord Baltimore, was born in London in 1629, and died there in 1714. Cecil sent Charles to Maryland in 1662, appointing him the governor. In 1675, upon the death of his father, Charles Calvert assumed the proprietorship of the colony, and became its sixth governor.

Charles Calvert (1637–1715), the third Lord Baltimore, in 1673. Living in the New World had its drawbacks. Note the square-toed, lace-up brogans. So 1672.

Charles Calvert (1637–1715), the third Lord Baltimore, in 1673. Living in the New World had its drawbacks. Note the square-toed, lace-up brogans. So 1672.

Article XVIII of the Charter of Maryland granted the Lords Baltimore full authority to "assign, Alien, grante, demise, or enfeoff" any parcels of land to any persons willing to purchase. Under this warrant, Cecil Calvert established the Conditions of Plantation, a system that defined the nature of ownership and title to land that transferred pursuant to the Charter. Essentially a title that passed from Cecil or his successors to a purchaser would be similar to what today would be called an assignable lease in perpetuity. The purchaser was entitled to do with the land as he pleased, and had the right to sell to another or pass it on by inheritance. However, he was required, as were subsequent purchasers or inheritors, to pay yearly rents to the Lords Baltimore, forever.

An English pioneer named Richard Taylor, a Quaker merchant, bought from Charles Calvert land north of the not-yet-existing boundary of Baltimore City for an unknown price. He later acquired several additional tracts of land, and consolidated the estate which came to be known as Taylor's Range. On Richard Taylor's death, the land passed by will to his son Joseph Taylor.

Joseph Taylor’s son, Joseph Taylor II, first built a log cabin on the property. By 1704, he had constructed the first section of the stone mansion that remains to this day. Joseph Taylor III, added additional sections to the house in 1770, and the estate was named Mount Pleasant by the family. After the Revolutionary War (which was won by the colonies), payment of yearly rents to the Lords Baltimore were no longer required, and possessors of land under the authority of the Charter of Maryland and the Conditions of Plantation were deemed by the new government to be the owners of that property in fee simple. Descendants of Joseph Taylor lived on the property until 1915, when the land was leased as a tenant farm.

Taylor's Chapel. (Click image to expand.)

Taylor's Chapel. (Click image to expand.)

Wholly within the boundary of Mount Pleasant Park lies a three-quarter-acre plot on which sits Taylor's Chapel and the adjacent Taylor's Cemetery. This essay was written by Barbara Nickel, chairperson of the Taylor's Chapel Board of Trustees, based on the research of Carroll Taylor Sinclair.

On August 13, 1924, the Park Board of Baltimore authorized the purchase of the property. Negotiations were held between Randolph Barton, Jr., representative of the Taylor family trusts, and J. Cookman Boyd, on behalf of the Park Board. (note) On February 24, 1925, the purchase was completed. The city acquired 260 acres, primarily woodland, for $130,000. The acquisition fulfilled the promise the Park Board had made three years earlier to the residents of Govans, that the next city park would be established within their district. The designer of Baltimore’s parks system, Frederick Law Olmstead, Jr., was a landscape designer lauded for his work in many cities. Use of the Taylor property as a park, although outside the city limits of his time, fit with the urban parkland scheme Olmstead had established for the city two decades earlier in his 1904 "Report Upon the Development of Public Grounds for Greater Baltimore."

The $500 per acre cost of the Mount Pleasant property was small in contrast to the cost of other property acquired for Baltimore parks up to that time. Patterson Park [128 acres] was bought for $3,632 per acre in 1827; Druid Hill Park [674.16 acres], was purchased for $1,069 an acre in 1860; Carroll Park [177 acres] cost the city $1,736 per acre in 1890; Clifton Park [267.26 acres] was acquired in 1895 for $2,822 an acre; Gwynn’s Falls Park went in 1902 for $1,000 an acre for 390.3 acres; Wyman Park [198.39 acres] became public property for $617 an acre in 1903; and Herring Run Park cost $680 an acre for 164.61 acres in 1908. The parcels comprising Broening Park, on the waterfront, were acquired over time [before 1924] at an average cost of $8,200 an acre.

The press release issued by the Baltimore Park Board announcing the purchase did not mention that a golf course would be built on the property.