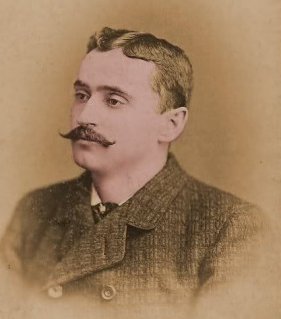

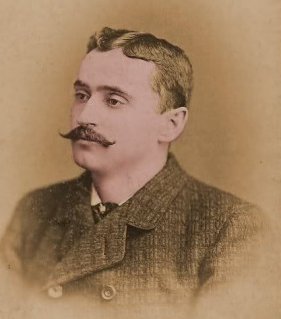

Edward Hugh (Ned) Hanlon | Mount Pleasant ParkGolf CourseMaryland's Tournament CourseEstd. June 30, 1934 | Charles Augustin (Gus) Hook |

Edward Hugh (Ned) Hanlon | Mount Pleasant ParkGolf CourseMaryland's Tournament CourseEstd. June 30, 1934 | Charles Augustin (Gus) Hook |

The city of Montrose, in County Angus, Scotland, is often mentioned in the long history of the game of golf. A Montrose resident named James Melville, in one of the earliest recorded golf writings in 1562, was said to have been taught from the age of six “to use the glubb for goff.” The city holds the distinction of having the first golf widow: In 1629, Magdalene Carnegie suffered the absence of her husband, James Graham, first Marquis of Montrose, as he played golf first before and then immediately after their wedding ceremony, and every day following on the two weeks of their honeymoon. The Medal Course in Montrose has been in continuous use for more than 450 years, and has hosted many Scottish professional, amateur, and open championships.

The Medal Course at Montrose

The Medal Course at Montrose

James Winton (1835-1907) was a golf professional and clubmaker of note in Montrose. Clubs made by him are prized by collectors. Winton made several clubs for Willie Park, winner of the first major championship in golf history, the Open Championship of 1860. Park won the Open three more times, the last in 1875. He also played often at Montrose courses, as did his son, Willie Park Jr. (1864-1925), who would win the Open Championship in 1887 and 1889.

Willie Park, Jr.

Willie Park, Jr.

James Winton’s son Thomas (1871-1944) was also a golf professional and clubmaker. His playing skills were less than championship caliber, and his clubmaking activity was confined to performing routine tasks in his father’s shop. In order to pursue his dream of designing golf courses, Thomas Winton moved to London around the turn of the century. There he was employed in golf-course construction, working for several architects in building such courses as Coombe Hill and South Herts.

The younger Willie Park’s primary occupational interest was the making of clubs. His designs were revolutionary, and he is credited with the introduction of clubheads with higher loft that launched shots higher and which would stop quicker when hitting greens. Park’s focus shifted over time, and he too developed an interest in golf-course design. When Park decided to take his design skills to the United States, he asked his old friend from Montrose, Thomas Winton, to join him.

Their partnership of Willie Park Jr. and Thomas Winton failed to flourish, however, and Winton soon found it necessary to secure a paying job as superintendent for the Westchester (New York) County Parks Commission, where he remained for many years. He was in charge of maintaining the county's golf courses and parks and with constructing new facilities. In this capacity he designed several public courses in the New York suburbs.

Winton soon found additional design jobs, and in the 1920s was active along the Eastern Seaboard, laying out courses and supervising their construction. When design business fell off in the Depression, he continued in his Parks Commission position and also served as a maintenance consultant for several New York golf clubs. Thomas Winton designed these courses between 1923 and 1929 in the United States:

Winton remodeled or expanded these courses:

Thomas Winton was retained to design the Mount Pleasant Park course. Although not certain, it is likely that Winton came to the attention of the Baltimore Park Board as a result of his work on the nearby Congressional Country Club championship course. That course, designed by Devereaux Emmet, opened in 1924. Thomas Winton was brought in to renovate the course so that it would provide a major test for the best golfers, and thus have a greater chance of achieving the membership’s goal of attracting the best national and international competitions.

The Blue Course at Congressional

The Blue Course at Congressional

Thomas Winton’s survey of the Mount Pleasant Park property concluded that the land would support no more than a nine-hole course. It appears, from the limited information available, that Winton concentrated his contemplated nine-hole course on land north of the mansion. It may be that he felt the streams to the south, Herring Run and Chinquapin Run, presented obstacles that would not allow golf holes to be built on the property near where they ran. Additionally, a 2½-acre parcel of land owned by Dr. Henry Barton Jacobs cut into the Taylor property boundary in such a way that it narrowed the land available on which to build. The Park Board negotiated with the doctor for the purchase of the land, and eventually the sale was completed, but it is likely that at the time Winton was designing the course, he had to assume that land would be unavailable.

Winton built a model of his nine-hole design, and construction began in late 1929. It is not now known if Winton was the superintendent of construction.

By June of 1931, only four fairways were ready for seeding, and only one green was near completion. The cost of the work to that point was $42,000. [Several 18-hole courses that Thomas Winton designed and built were completed at costs between $40,000 and $45,000.] The superintendent of parks at that point called the whole thing off, saying that “independent golfers and members of golf associations looked over the work and raised a howl.” Whether the collective howl was caused by Thomas Winton’s design, the quality of the work, or the slow progress of it, is not known.